Choice is about considering a situation we find ourselves in or an opportunity that has presented itself where there are multiple outcomes possible, depending on what path is chosen and implemented. We might consider going out on a date with someone; the choice will be very different depending on whether we are currently single and seeking a potential mate, are recently separated or widowed, we are already partnered or are a single parent. We might be offered a new job role, or business opportunity – again, depending on what is at risk, what we currently need to attend to, what looks like a grand opportunity might actually be a huge risk or even a big waste of time.

I acknowledge that there are many societies where this kind of choice and this range of options are not available, for example, for many women in non-Western societies. While it makes me very sad to acknowledge this, I cannot address the complexities of choice in those contexts where human rights abuses and cultural mores place restrictions on individuals’ capacity and freedom to freely choose their own life path. This article addresses itself to men and women who live in societies where they are relatively free to determine the course of their lives in relation to their health, work, relationship and family, and financial choices. Choosing wisely requires us to take a very active role, mentally exploring the various implications of what the various options might be, how those outcomes might affect us and others in our lives, what resources we will need in order to pursue each path under consideration, where we might source the resources and skills we need if they are missing from our repertoire, and what the costs and risks will be in choosing to pursue each option.

I acknowledge that there are many societies where this kind of choice and this range of options are not available, for example, for many women in non-Western societies. While it makes me very sad to acknowledge this, I cannot address the complexities of choice in those contexts where human rights abuses and cultural mores place restrictions on individuals’ capacity and freedom to freely choose their own life path. This article addresses itself to men and women who live in societies where they are relatively free to determine the course of their lives in relation to their health, work, relationship and family, and financial choices. Choosing wisely requires us to take a very active role, mentally exploring the various implications of what the various options might be, how those outcomes might affect us and others in our lives, what resources we will need in order to pursue each path under consideration, where we might source the resources and skills we need if they are missing from our repertoire, and what the costs and risks will be in choosing to pursue each option.

Elsewhere, I have written about choice architecture and ways of setting one’s self up to make better choices[i]. The issue is: how do we work out what are ‘better choices’ for us?

In the Western world, most of us have many choices we face each day, each week, over the year, over the course of our lives. Most of us are free to choose: who to partner with; whether to have children; what sort of career to have/ whether to retrain and change careers; where to live; whether to buy or rent; where to travel; how to spend our money; how to spend our leisure time; how to spend our time and so on. For many of us in the West, the list of choices is endless. The choices we face and consider relevant are, in part, affected by what stage of life we are at – whether to go on a gap year of travel after high school; whether to drastically change direction and leave a carefully built career path; whether to have children or remain childfree; whether to take in an elderly parent and care for them in one’s home; whether to save up for one’s retirement, or buy a home; whether to sell up and move to a more ability-friendly facility with failing health or greater age.

In the Western world, most of us have many choices we face each day, each week, over the year, over the course of our lives. Most of us are free to choose: who to partner with; whether to have children; what sort of career to have/ whether to retrain and change careers; where to live; whether to buy or rent; where to travel; how to spend our money; how to spend our leisure time; how to spend our time and so on. For many of us in the West, the list of choices is endless. The choices we face and consider relevant are, in part, affected by what stage of life we are at – whether to go on a gap year of travel after high school; whether to drastically change direction and leave a carefully built career path; whether to have children or remain childfree; whether to take in an elderly parent and care for them in one’s home; whether to save up for one’s retirement, or buy a home; whether to sell up and move to a more ability-friendly facility with failing health or greater age.

In the West, we make our choices in a context that constantly exhorts us to buy, buy, buy; to have as much material stuff as possible, and tells us we must always aim to have the latest model; to get things as fast as possible; to compare ourselves and our lives to others and their lives; to look a certain way; to date a certain type of person; to ‘be connected’ (technologically); to live as though there will be no death; to look as young as possible for as long as possible by almost any means; and to ‘have it all’. Our gender socialisation, our family of origin and our family’s expectations; our sexual orientation; our racial, cultural, political and religious backgrounds; our socio economic backgrounds and privilege; our level of health and physical ability; the society we live in – all of these play a part in influencing us in our efforts to discern what are the ‘right’ choices for us to make.

In the West, we make our choices in a context that constantly exhorts us to buy, buy, buy; to have as much material stuff as possible, and tells us we must always aim to have the latest model; to get things as fast as possible; to compare ourselves and our lives to others and their lives; to look a certain way; to date a certain type of person; to ‘be connected’ (technologically); to live as though there will be no death; to look as young as possible for as long as possible by almost any means; and to ‘have it all’. Our gender socialisation, our family of origin and our family’s expectations; our sexual orientation; our racial, cultural, political and religious backgrounds; our socio economic backgrounds and privilege; our level of health and physical ability; the society we live in – all of these play a part in influencing us in our efforts to discern what are the ‘right’ choices for us to make.

A client came this week personifying this dilemma. At 36, she is an educated professional woman, working at a prestigious university, pursuing another degree, pursuing creative interests, and recently partnered in a loving relationship. She told me she feels exhausted as she tries to attend to all the things in her life that matter to her – her research, her work as a university lecturer, her relationship, and her own creative practice. However she tries, she feels she is failing. She mourns the fact she is not really seeing much of her friends right now, and she worries that she spends what little time she has that’s unstructured recovering her energy reserves or ‘just’ with her partner. Meanwhile, a nagging internal voice attacks her for ‘not being interesting enough’, ‘not living a vital enough life’, not living a ‘full enough life’, and ‘not cooking interesting enough meals’ for her partner when she does cook for him. All of these self- reproaches have a very familiar ring to me.

We spent some time looking at the issue of values as a possible key ingredient in helping her arrive at some useful way of discriminating choices available to her and finding a way to make peace with her choices. Values are the principles we hold for ourselves or standards of behaviour we believe we (and perhaps others too!) ought to live by in certain areas of life; they are the judgement we make about what is important in life. When people talk to us about their values, it’s useful to think of them as referring to a continuum – from the ‘good to have in principle/ not necessarily lived by’ all the way to ‘can’t live with myself easily if I don’t abide by this’. Core values are the most significant values we hold that we feel deeply uncomfortable about deviating from. Core values tend to be stable, irrespective of what context we are in. When we deviate from them for a time, calling them up and reviewing what they mean to us can help us make necessary course-corrections in our lives that help us feel at ease with ourselves.

When we use our core values in a situation to assist us in making choices about how to be and act, then our decision-making process can become guided by the core values that apply in our eyes at a particular time in any one circumstance. What does not fit our core values then does not get chosen, even if it is pretty, sexy, glamorous, tasty, fun, different, interesting, or makes us look cool.

I laid out for her what I consider to be a few basic truths –

- Every choice precludes others – no we can’t have it all! We can’t have an affair, not even a one-night stand, and expect our monogamous partner to be okay with that or not react and stay afterwards if they find out;

- Part of the limits we face on the choices available to use pertain to our having limited amounts of time available, limited energy, as well as limitations on our ability to stretch ourselves across multiple areas of our lives and still feel good.

- In some situations, we may want different things at the same time, and some of these might be incompatible. We can see this as partly due to the fact that we are complex creatures who have many different aspects that make up who we are, all of which seek to have their priorities met: we might be a serious student who wants to party; a responsible family man who wants to disappear and wander around the world; a peace activist who loves watching violent films and so on. This is where values can help us determine what’s essential, from what’s ‘nice to have’

- Not all choices are equally important or of equal value at different points in our lives. Yes, when we are sixteen, the prom is a live or die affair in some countries and some strata of society; going to a dance party and having party drugs might seem like a great idea and sound like fun at some stage of our life, but it might not be wise if we are studying for exams the next day, or we are currently dealing with having a newborn baby in the house. It might be great to attend the last concert tour show of our favourite artist, but it might not be so great if it means we choose to not be with a beloved friend at a time in their life when things are tough. Unprotected sex with a casual partner might feel physically tempting in the moment, but the potential for dealing with STIs and or lasting fertility issues (not to mention pregnancy) later are worth bearing in mind.

In our society, with the constant presence of advertising and social media in many peoples’ lives, it’s easy to get caught up in FOMO – Fear Of Missing Out. Well, yes: it’s a reality we all need to face if we are to live like grownups: we all miss out. All of the time. In choosing to do one thing and not another, we miss out on the other. In choosing one career path, and not another, we miss out on the other. In choosing one partner, and not another, we say no to other partners. In choosing to have children, we choose to have a different range of freedom about how we spend our time and resources.

In our society, with the constant presence of advertising and social media in many peoples’ lives, it’s easy to get caught up in FOMO – Fear Of Missing Out. Well, yes: it’s a reality we all need to face if we are to live like grownups: we all miss out. All of the time. In choosing to do one thing and not another, we miss out on the other. In choosing one career path, and not another, we miss out on the other. In choosing one partner, and not another, we say no to other partners. In choosing to have children, we choose to have a different range of freedom about how we spend our time and resources.- Our society actively stirs up the part of us that’s susceptible to FOMO, often as a marketing strategy to get us to buy their product. Ask yourself – how old is that part? Is it fair to say it’s a part of you that was once susceptible to the kind of “I’m better than you/ I’ve got something you haven’t got” games we all experienced in the school playground? Is that really the part of you you want to have running the show making decisions that direct your adult life today? Maturity, among other things, is about accepting the reality that every choice precludes others, and that’s not only a fact, it’s not a bad thing. Resist the framing of ‘missing out’ as a bad thing – consider framing what you say no to in your own mind as what you have considered and discarded for your own reasons – then watch the so-called fear of missing out fall away. There is no FOMO in consciously owning the choices you make. Ask someone who has experienced anaphylactic shock from eating peanuts!

- There is an argument also for it not being a bad thing that we cannot have everything we say we want. Observe the antics of super-privileged celebrities depicted in the media if you doubt that. Having all the money or power that one could wish for does not make for happier lives – look at the World Happiness Report [ii] .

Deciding whether a choice might be the right one in any one moment has to be considered within the longer term context beyond the moment as well. This involves being able to pause the moment of decision-making at times to consider the bigger picture, weighing up other peoples’ interests as well as our own longer term best interests in the process of deciding what’s more important, knowing we can’t have it all. Will this ice cream impact our food choices on our weight reduction food plan? Will ‘trying’ injecting heroin once potentially have consequences for the choices we make in the future? What will doing one more thing on our email mean to our child if we turn up late to pick them up after school over and over?

Deciding whether a choice might be the right one in any one moment has to be considered within the longer term context beyond the moment as well. This involves being able to pause the moment of decision-making at times to consider the bigger picture, weighing up other peoples’ interests as well as our own longer term best interests in the process of deciding what’s more important, knowing we can’t have it all. Will this ice cream impact our food choices on our weight reduction food plan? Will ‘trying’ injecting heroin once potentially have consequences for the choices we make in the future? What will doing one more thing on our email mean to our child if we turn up late to pick them up after school over and over?- In order to determine what has more worth to us, more value to us in any one set of circumstance, we need to be aware of what our core values are: what are the core principles by which we might want to guide our choices about how to be, how to relate to others, and how to operate in the world. These can help us to see past our situational attractions and aversions, our desire for self gratification, greed, competitiveness or revenge, and our impulsiveness. They can help us make wiser choices that we would not ordinarily make if we just followed our impulsive reactions, or our short sighted judgement calls to determine our decision-making in the moment. They enable us to take a wider view of our situation, consider the wider implications of the choices we might make, both for us and for others, and to arrive at an ‘on balance’ decision we can live with for the long haul.

- Fact: we have limited amounts of energy and time. Even if we try to artificially boost and deny this reality with No-Doze, copious quantities of caffeine, and so–called energy drinks, we will still head for trouble if we insist on ignoring our bodies’ energy and reserve limits. If we don’t rest, eat reasonably well, and manage our energy, it will catch up with us at some stage;

- As with money, in relation to energy, we need to have some sort of budget in mind that tracks our incomings and outgoings, our energy debt and our energy reserves. We need to be mindful of not only the current things we want to focus on that are important to us and the amount of focus and energy they require from us, but also what our remaining energy levels are from our recent ‘expenditure’, as well as what planned activities that lie ahead are going to require from us.

- Given the above, we need to budget how we allocate our focus, our energy, our time, our presence. We need to make decisions about how we might best allocate our limited resources according to whatever priorities we have in our present life. What is the best use of our energy given our limitations as a human being, given our current priorities, and given our priorities to come?

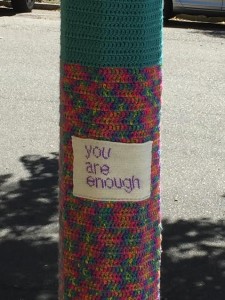

Then, there is the internalised pressure of objectification. Whether coming from our inner voice that constantly compares us to some mythical standard and tells us that we are not enough, not doing well enough, not making a good enough effort, and not measuring up, or from external sources such as social media or friends and acquaintances, there is a huge trend to objectify ourselves and to be objectified. In the process, we treat ourselves as things, objects, projects, to be manipulated, shaped, used, and judged. We can fall in the trap of treating ourselves as though we are disposable. We can end up not treating ourselves with the care, respect, sensitivity and compassion we would extend to a person we cared about, losing sight of the context of our day to day existence, and not accepting ourselves for who we are.

Then, there is the internalised pressure of objectification. Whether coming from our inner voice that constantly compares us to some mythical standard and tells us that we are not enough, not doing well enough, not making a good enough effort, and not measuring up, or from external sources such as social media or friends and acquaintances, there is a huge trend to objectify ourselves and to be objectified. In the process, we treat ourselves as things, objects, projects, to be manipulated, shaped, used, and judged. We can fall in the trap of treating ourselves as though we are disposable. We can end up not treating ourselves with the care, respect, sensitivity and compassion we would extend to a person we cared about, losing sight of the context of our day to day existence, and not accepting ourselves for who we are.

A client of mine was telling me about his wife’s reaction shortly after the difficult birth of their first child where she had accepted pain reducing medication; this had not been in her birth plan. As she lay there exhausted after this massive challenge, with her partner by her side and her new baby on her belly, she was speaking out loud the kind of tormenting thoughts she was plagued by. She spoke at length about how bad she felt for having taken ‘drugs’ and not having managed to achieve the ‘natural birth’ she had so wanted and planned for. In the moment, until he called her back to reality with a passionate plea of ‘Please don’t do this: not after I’ve just watched you do the most amazing, difficult, bravest thing I’ve ever seen anyone do, ever!” she was robbing herself of the joy of being present with her baby, with her partner, sharing what ought to have been incredibly precious moments of relief, pride, gratitude, happiness, pleasure, and love. Instead, she was locked in to a self-attacking exchange with her inner critic, objectifying herself against some mythical standard of what her birth process ‘should have been like’. Where is the reality in that? Where is there any recognition that our choices and what we do are determined in part by how life unfolds as we go, and our resources at the time? Where is the recognition that context has to play a part in how we view what we choose to do? And where is the recognition that we are human, and we are not meant to be living the kind of unrealistic lives that our inner critics push us to have and claim to be possible?

In the throes of being caught up in self-objectification, we abandon our lives and the present moment. Instead, we engage in feeling less than, not good enough, and we end up spending more energy, time, focus, and mental and emotional energy on what we didn’t do/ who we are not/ what we didn’t choose, than on what we are doing/ choosing, and who we are.

If these comments resonate for you, I urge you to consider the following when you find yourself struggling over not being enough/ not doing enough/ not doing things well enough, and wondering what is the ‘right’ choice for you in some area of your life. Ask yourself:

- What are my core values?

- What core values does this situation call on me to choose?

- Right now, in this situation , which of my core values am I choosing to attend to and which other values (and therefore options) am I consciously choosing to set aside for now?

- If you still feel torn by the choice, how will I feel in a year’s time, five years’ time about the choices I made and how present I was for my own life and my relationships with others at this time of my life?

And if you feel you would benefit from some support in working through some tough decisions in your life right now, then call me.

[i]https://mariepierrecleret.com/blog/new-years-resolutions-2016/

[ii] http://worldhappiness.report/